As Ireland’s tourism sector barrels toward 2026 with the kind of ambitious momentum that would make even the fiercest Atlantic gale seem tame, the Emerald Isle is banking on its untamed western coastline to deliver an experience that transcends the usual postcard clichés of shamrocks and Guinness.

The Wild Atlantic Way, a serpentine 2,500-kilometer route hugging Ireland’s western edge, has become more than a scenic drive; it’s now the economic engine sustaining 80,000 jobs and pumping €3 billion annually into communities that would otherwise watch their young people flee to Dublin or beyond.

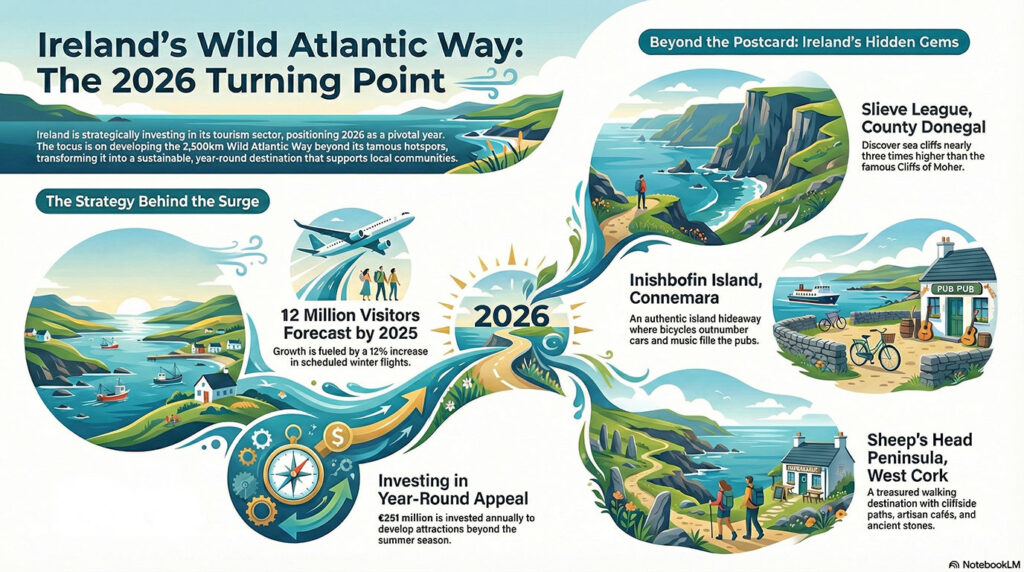

The numbers tell a story of calculated ambition. Ireland welcomed 11.3 million overseas visitors in 2024, already surpassing pre-pandemic levels, with forecasts pushing toward 12 million in 2025 and continued growth into 2026. This isn’t organic happenstance, it’s the result of 12% more flights scheduled for the 2025–26 winter season and a government hell-bent on hitting €9 billion in tourism revenue by 2030, a 50% jump that requires making the country not just visitable but irresistible year-round.

Ireland’s tourism surge to 12 million visitors isn’t accidental, it’s engineered through strategic flight expansion and calculated infrastructure investment.

Which brings us to 2026, a year positioned as the inflection point where infrastructure meets intention. The state is pouring €251 million annually into tourism development (though operators are clamoring for more), targeting a 5% expansion in everything from hotel beds to indoor attractions that can showcase Ireland’s appeal when the weather lets be honest turns properly miserable.

The strategy acknowledges what seasoned travelers already know: relying solely on summer crowds creates feast-or-famine economics that benefits no one, least of all the communities actually hosting these visitors.

The Cliffs of Moher remain the undisputed headliner, drawing 1.6 million people annually to stand at those vertiginous edges where land capitulates to ocean in dramatic 200-meter drops.

But the real shift involves diversifying beyond such tentpole attractions, developing projects that encourage visitors to linger in shoulder seasons, those changing weeks when crowds thin and the landscape reveals its more contemplative moods. Campaigns promoting Ireland as the “Home of Halloween” and emphasizing natural scenic routes represent attempts to reframe the country’s appeal beyond green fields and Celtic mysticism. The premium traveler segment is being particularly courted, with operators developing bespoke experiences ranging from luxury coastal accommodations to gourmet food tours that cater to high-spending visitors seeking immersive, personalized adventures.

And this is precisely where Ireland’s lesser-known wild spaces begin to shine.

Ireland’s Hidden Wild Atlantic Wonders

While the star attractions absorb the spotlight, 2026 is shaping up to be the year curious travelers start seeking out Ireland’s quietly spectacular corners, those places the tour buses breeze past, but the locals speak of with a soft, knowing pride. These under-the-radar stops not only relieve pressure on hotspots like the Cliffs of Moher or Killarney, but also offer more intimate, slow-travel experiences aligned with Ireland’s changing tourism landscape.

One such gem is Slieve League in County Donegal, one of the highest accessible sea cliffs in Europe, soaring to nearly three times the height of Moher yet drawing a fraction of the crowds. The clifftop trails and viewing platforms offer some of the most dramatic coastal scenery on the island.

👉 https://www.sliabhliag.com/

Further south, Inishbofin Island off Connemara remains one of Ireland’s most soulful hideaways, a place where time stretches, bicycles outnumber cars, and the Atlantic soundtrack never stops. Its coastal trails, Iron Age forts, and music-filled pubs lure travelers seeking authentic West of Ireland charm without the rush.

👉 https://www.inishbofin.com/

For those drawn to raw landscapes, the Derrigimlagh Bog Discovery Point in Connemara feels utterly otherworldly. This windswept stretch of blanket bog punctuated by shimmering pools and low-lying heather was the landing site of Alcock and Brown’s world-first transatlantic flight. A serene boardwalk walk interprets both nature and history.

👉 https://www.galwaytourism.ie/derrigimlagh-discovery-point/

In West Cork, the Sheep’s Head Peninsula remains one of Ireland’s most treasured hidden peninsulas, a narrow finger of land dotted with artisan cafés, ancient standing stones, and cliffside paths leading toward the iconic lighthouse. It consistently ranks as one of the country’s best walking destinations.

👉 https://www.sheepshead.ie/

Even off the main coastal artery, the Wild Atlantic Way’s inland pockets hold treasures. Gleninchaquin Park in County Kerry feels like a private valley: cascading waterfalls, wooded trails, and open farmland where only skylarks and sheep share the view.

👉 https://www.gleninchaquinpark.com/

These are the kinds of places that will define the Wild Atlantic Way’s next chapter, slower, deeper, more personal.

Why 2026 Is the Turning Point

What makes 2026 particularly compelling is this convergence of capacity and capability. Two-thirds of tourism revenue flows from international visitors, mainly North Americans and mainland Europeans, who are being strategically encouraged to extend their stays beyond Dublin, where only 31% of tourism jobs exist anyway. With the sector already supporting 260,000 jobs nationwide, this expansion represents a significant opportunity for coastal and rural employment growth.

Dublin’s coastal makeover is further enhancing this distribution, with its expanding Dublin Coastal Trail drawing visitors outward toward Howth, Dalkey, and beyond.

The domestic market, meanwhile, is being nudged toward short breaks during off-peak periods, creating a more sustainable rhythm of visitation that smooths out seasonal spikes.

Ireland’s wild side has always existed; those storm-battered headlands and boggy expanses never needed marketing copy to justify their existence.

But 2026 represents the moment when experiencing them becomes less about fighting infrastructure limitations and more about choosing which perfectly positioned accommodation to book, which newly developed attraction to prioritize, and which revitalized coastal town deserves an extra night.

In other words, the Wild Atlantic Way is no longer simply a scenic drive, it’s becoming a year-round lifestyle experience.